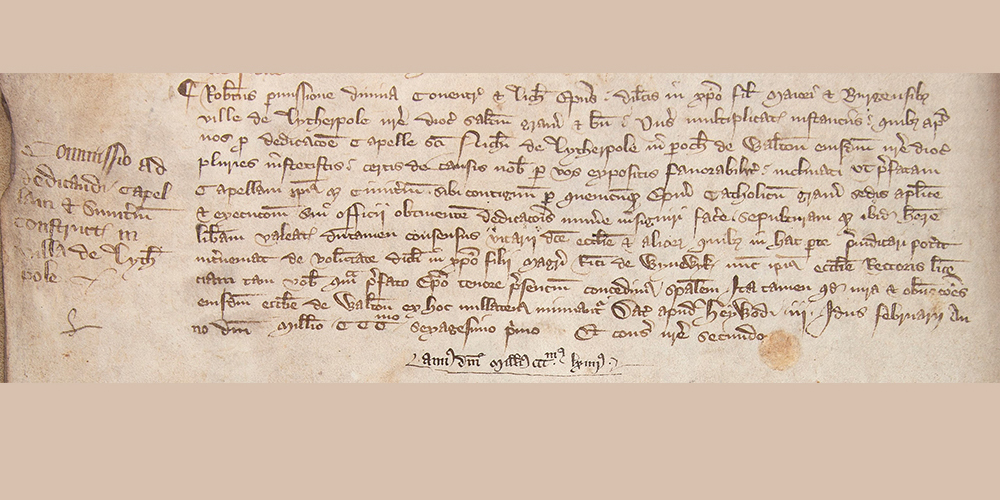

Licence from the Bishop of Chester to consecrate a new Chapel in February 1361/2

Liverpool Parish Church stands at the heart of the business centre of the city, looking

across the River Mersey, and adjacent to the Liverpool Waterfront. There has been a

place of worship on this site for more than 750 years.

Remains of the medieval church can still be seen in the foundations of the 19th century tower

The original chapel of St Mary Del Quay, (believed to be situated near to the present day Maritime Chapel) is first mentioned in records in the mid-thirteenth century. There is no certainty about when it was built or who built it, but we know it was used a chapel of ease for the main Parish Church which is situated about four miles away in Walton in north Liverpool.

By the mid-fourteenth century the population of Liverpool had grown to about 1,000 people and an outbreak of plague prompted the consecration of the church yard for burial. Around the same time in 1361/62, a larger chapel was constructed and dedicated to St Nicholas, patron saint of mariners. At least one guide book to the city, dating from the late-18th century talks about a statue of St Nicholas in the church yard to which the sailors presented offerings before going to sea.

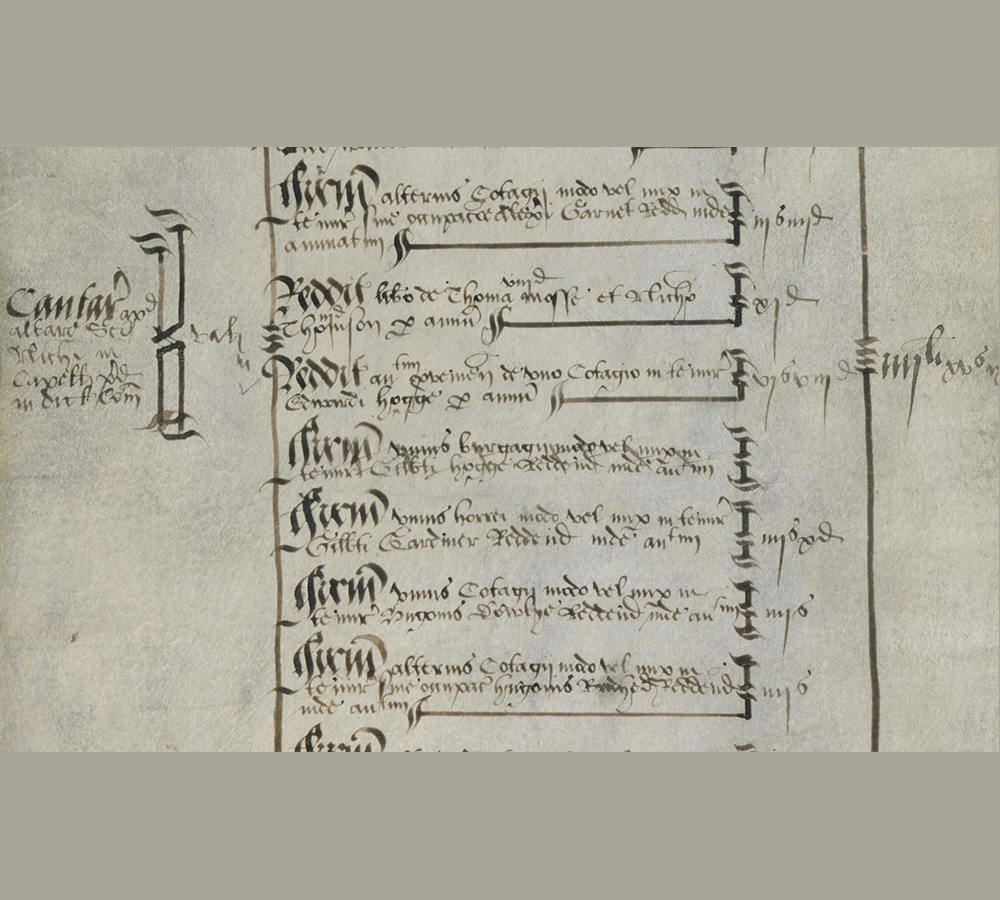

At the Reformation the Duchy of Lancaster sold land from the chantries to Richard Molyneux

During the later Middle Ages the City of Liverpool grew. In the late 15th century the existing chapels were unified and the church doubled its size with the addition of an aisle and further chantry altars. The dual dedication to Our Lady and St Nicholas dates from this period, but there were four chantries attached to the Church. The first Chantry dedicated to St John dates from the 1320s (founded by John Liverpole); the second dates from shortly after this and was dedicated to St Mary (founded by Henry, Duke of Lancaster); the third dated from the 1360s and dedicated to St Nicholas (founded by John of Gaunt); and the final one dedicated to St Katherine and established by the will of John Crosse in 1515.

A national inventory of church goods made at the time of the Reformation (mid-sixteenth century) shows St Nick’s was more substantially and lavishly furnished than the mother church at Walton. It was also used for more than just religious purposes. The town held meetings there, local taxes and transactions were collected there and in the late-16th century sail making was taking place, the church being one of the largest and driest places in the town (although this practice was later condemned by the town’s authorities).

Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

Liverpool was a key town in the Civil War, but a brief period of puritan dominance subsided at the Restoration when the Town reasserted the position of its church. In 1699, the Parish of Liverpool, with a population of about 5,000, was created as an independent parish in its own right and had two churches: Our Lady and St Nicholas (often called the ‘Old Church’ or St Nicholas) and a new parish church of St Peter (1704). The new parish had the highly unusual arrangement of having two Rectors, who were to be of equal status. They alternated churches on an annual basis until more modest arrangements were made for a single Rector of Liverpool from 1855.

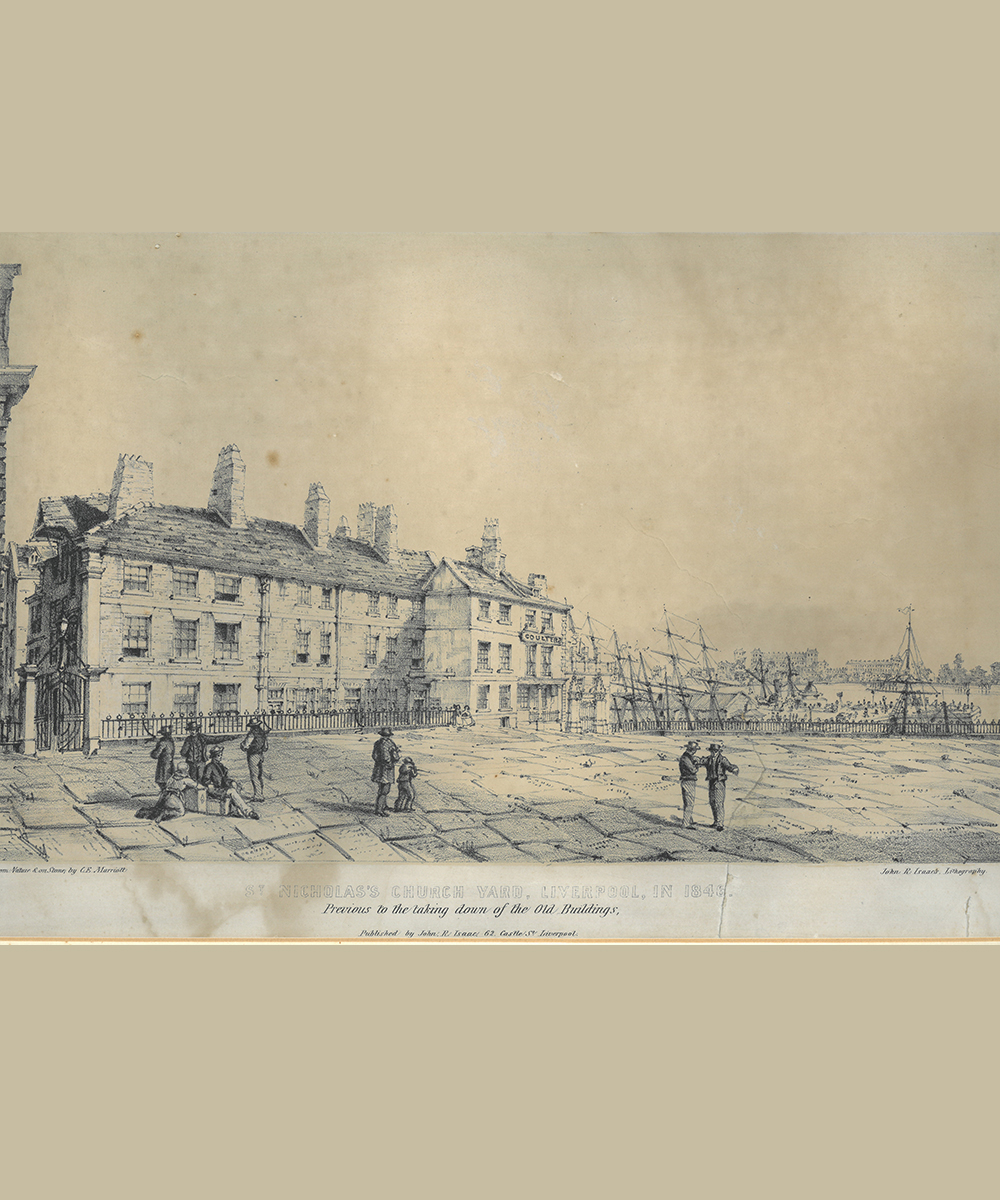

In 1747, a spire was added to the existing tower of the church, and in 1749 the churchyard was extended by the addition of a piece of land reclaimed from the river due to the construction of a sea wall. It is hard to imagine now, but before the land was reclaimed during the late-19th century to make a space for the present Liver Building, the river and dock system actually came right up to the boundary wall of the church.

George’s Dock, which was the third dock to open (in 1771), was immediately outside the church and was the resort of ships arriving largely from the West Indies. A merchants’ coffee house stood in the church yard (possibly in the former chapel building of St Mary del Quay) which had commanding views of the river. Thoroughfares passed in every direction through the church yard which created an atmosphere of hustle and bustle, far removed from the traditional quiet place of solitude and reflection anticipated in a church yard.

The churchyard was the main burial ground for Liverpool for 500 years

Although the churchyard was well used, by 1775 the fabric of the building was reported to be in a ruinous state. An unusual approach to its redevelopment was adopted, with the decaying roof and walls being dismantled, and the new church building constructed around the existing tower and also the pews (whose owners forbade their dismantlement).

A significant factor in Liverpool’s growth in this period was the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and the trade in cotton, sugar, and other goods which were the produce of labour. We acknowledge our own part in that horrific trade: many clergy within the parish and dozens of churchwardens, sidesmen and overseers of the poor were connected with the trade. An early Rector, Robert Styth, even founded the Blue Coat Hospital (now School) with prominent slaver Bryan Blundell.

As the City grew, many new churches were built within the Parish, and by the mid-nineteenth century there were over thirty of them. Some of them ran fairly independently, but others remained under closer control from the centre. The Liverpool Vestry was one of the largest in the country: as well as overseeing the workhouse, it was also responsible for establishing the police and fire services in the town.

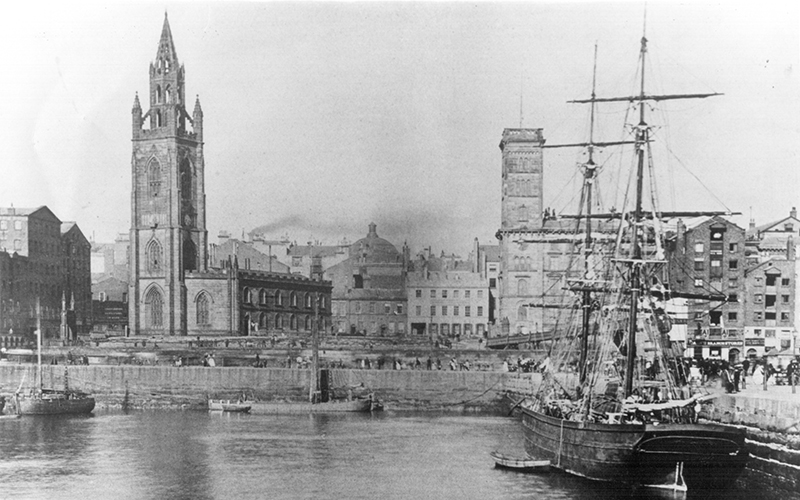

The earliest known photograph of the Church in 1871

Neglect to maintain the tower of St Nicholas resulted in its failure in the early-19th century: it collapsed in 1810 as the congregation were assembling for morning prayer, and 25 people, including 17 girls from the Moorfields Charity School, were killed. A new tower was subsequently designed in 1815 by Thomas Harrison of Chester. At the end of the 19th century the advowson (the right to appoint the Rector) was purchased by William Gladstone, four times Prime Minister. His descendants continue to appoint the Rector today. Many of the churches within the Parish either became parish churches in their own right, or were closed and demolished. St Peter’s, which had opened as the Parish Church in 1704 a, served briefly as the Cathedral following the creation of the Diocese of Liverpool in 1880. With the building of Liverpool Cathedral, St Peter’s closed, and Our Lady & St Nicholas once again became the Parish Church of Liverpool in 1916.

Apart from a significant refurbishment in the 1850s, from 1815 until 1927 the fabric of the building was little changed. In that year an administrative block, which now includes the Parish Centre, was added. On 21st December 1940, the church was hit by incendiary bombs during an air raid, and in the blaze which followed, the church was destroyed. Only the tower and the administrative block were unscathed. A great many interesting memorials to individuals and families important in the early history of Liverpool were lost, along with a set of stained glass windows, many of which also had historical links. Throughout the war, worship continued in the ruins and in a series of temporary buildings erected on the site. The old tower and spire escaped serious damage and were incorporated into a new church built to the design of Edward C Butler and consecrated in 1952 on the Feast of St Luke (18 October).

After wartime bombing, the new church was consecrated in October 1952

The rebuilt Church established its place again in the centre of the City. Few changes were made until 1993 when a major re-organisation of the administrative block was undertaken, and at the same time the chapel in the north aisle was reordered to become the Maritime Memorial Chapel; Princess Alexandra opened the Parish Centre in the same year.

Today the Tower continues to appear on maritime navigation charts, even though there are taller buildings around us. This is not the only way in which the church’s strong maritime links continue. Every year a number of maritime groups come to the church for services. At the same time, St Nick’s is at the heart of the business and commercial districts and also serves as the main civic church. The building and Gardens continue to develop and find new uses.

St Nick’s remains one of the most prominent churches of the North West. In the 20th century, six Rectors of Liverpool became bishops and one became a Cathedral Dean. One curate, Michael Ramsey, became Archbishop of Canterbury, and a number of other curates have gone on to be Deans and Bishops. Today the Church is one of the Major Churches of the Church of England, but locally it is still one of the most significant buildings in Liverpool’s heritage. As visitors to the city today once again turn their attention to the waterfront, St Nick’s remains where it has always been: the last sight you see as you leave the shore, and the first sight you see as you return.